From Standard to Response: How Listening For Nouns During Site Walks Will Open Your Eyes to What Students Need for State and National Tests

Welcome back! Last week, we discussed how a quick walk around your campus could give you tremendous insight into the type of language students are asked to produce during lessons and its correlation to current testing requirements.

We received many emails and comments from site principals who found that by following the simple analysis and teacher tips associated with the data collection, they were able to see immediate increases in academic language use by students.

This week, we are going to show how looking for and listening for something as simple as nouns will provide your teachers with key information about the connection between their posted objectives, their actual instruction, and student test performance.

Background

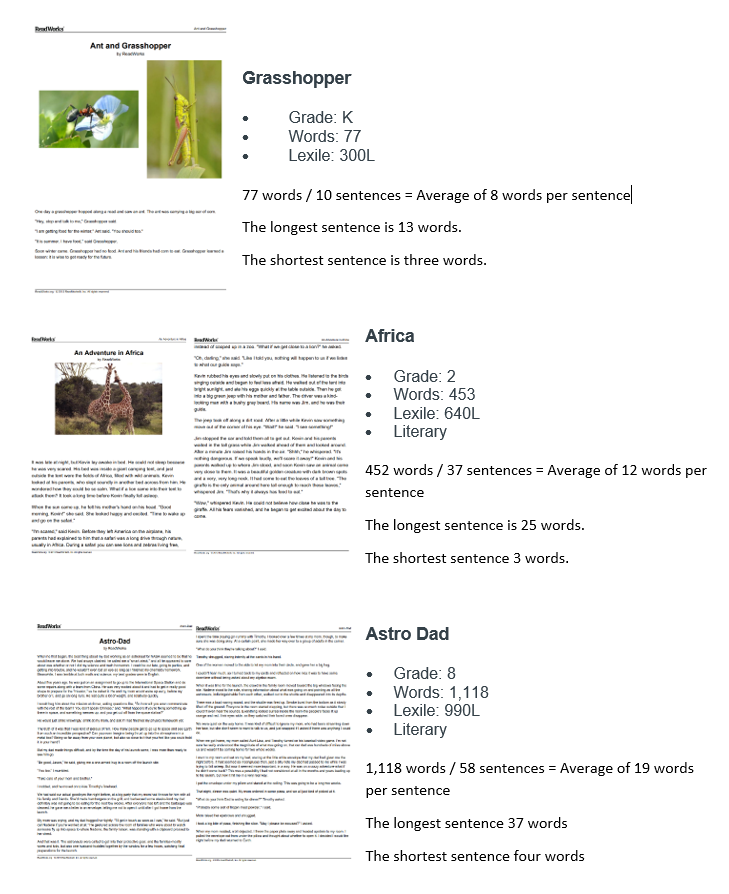

For years, teachers have been required to post objectives that guide the focus of classroom instruction. Frequently based on state standards, these objectives also provide a huge clue to how students will be assessed, especially when we look at the language structures used.

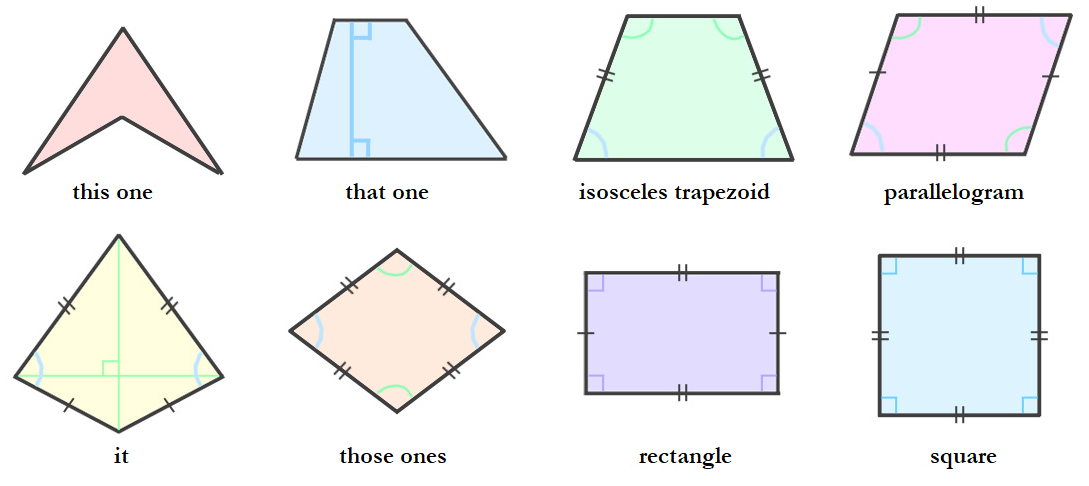

Every objective contains targeted academic nouns. These are specific words for concepts and ideas that are not typically used by students in regular conversation. These words represent one of the simplest, yet most vital, connections that must be made by teachers in order for students to understand and properly respond to test prompts.

The diagram illustrates this critical nexus.

So what is the problem with this interchange and how does it not prepare students to successfully address the types of questions they will see on state and national tests?

Let’s look back at the targeted academic nouns in the lesson objective. These nouns represent the core of the standard and should therefore be able to be tracked through each link in the chain.

Much like a baton in relay racing, the nouns in the objective should be used at each stage of the instructional cycle: objective, teacher questions, student answers.

In the example above, we can see that this sequence broke down early. What started as a well-planned lesson unintentionally digressed into an activity that bears little to no relation to the skills students will be required to demonstrate on state and national assessments.

By listening for these nouns, which often represent the targeted academic terminology that will show up on state and federal tests, you can easily and quickly see if students are being asked to utilize language skills that will directly impact their achievement.